The debate on single versus twin engines for fighter aircraft continues. Paul Stoddart* follows Gen Chuck Horner and David Baker, PhD into the ring.

The choice of engine is a fundamental design driver for any aircraft – both the type and the number. One or two engines and one or two seats are fundamental choices for fighter aircraft. However, while a second seat can be spliced into even smaller designs, the number of engines is fixed (the metamorphosis of the twin F-5 into the cancelled single-engined F-20 is an exception).

After decades of study and experience, the debate on one versus two engines continues. General Charles Horner, USAF, offered his views in the October ’98 issue of Air Forces Monthly, with Dr David Baker adding to the debate in the June ’99 issue of Air International.

General Horner emphasised the increasing reliability of engines and the lower cost of single-engine designs. Dr Baker balanced that approach by highlighting the unique performance advantages of twin-engine layouts. Two engines have a safety advantage over singles, but they are not major advantages, and the price paid for them is high. Indeed, General Horner argued convincingly that even with its likely higher lifetime losses due to engine failure, the single-engine fighter fleet would still work out cheaper. But will the superior aerodynamic performance of the twin help it gain air supremacy? If so, the extra cost will be money well spent – there is nothing more expensive than a second-rate fighter. Of course, there is more to air supremacy than manoeuvrability. Radar and missile performance are crucial, effective command and control is a force enhancer, and signature control is increasingly important.

Over the next few decades in the West, we may well see the service entry of the twin-engined GCAP, FCAS and whatever the US goes for. The current twin-engined designs are the F-15, Super Hornet, Rafale, Typhoon and F-22; the F-35, F-16 and Gripen represent the single-engine design school.

When a new aircraft is chosen, the engine number will be one of several fascinating design drivers. While a second seat can be spliced into even the smaller designs (Gripen and F-16) engine number is almost invariably fixed (F-20 weirdness aside). Cost and survivability are leading factors in the engine number debate, but there are two other issues: availability and commonality. Specifically, which engine types are available for use, and which do you already use? These points largely arise from the cost question but should be examined in their own right.

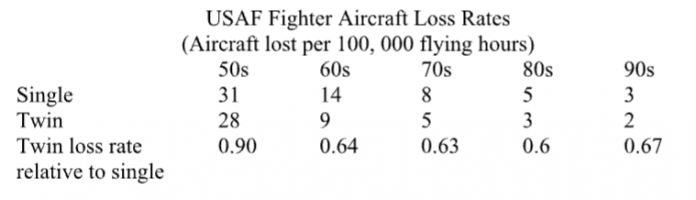

It is beyond argument that twin-engined fighters cost more to buy and support than their single-engine equivalents. The twin-engine proponents claim improved survivability in peace and wartime flying, justifying the extra expense. A commonly quoted statistic is that the extra engine buys around 15% lower attrition in combat. General Horner quoted the loss rates for US fighter aircraft from the ’50s to the ’90s (presumably peacetime losses). He correctly emphasised the major improvement for both types but then stated that the difference has narrowed significantly. The difference in raw numbers has fallen from a high of 5 in the ’60s to one in the ’90s. However, the proportional difference, i.e. the relative likelihood of losing an aircraft, should also be considered. In that respect, a twin was little better in the ’50s than a single, suffering 90% of the latter’s loss rate. However, for the following four decades to the late 1990s, the twins had an average loss rate of 64% of the single.

The twin’s advantage may appear valuable, but remember that the raw numbers are very small; this has two effects. The loss of one more aircraft of either type can sway the relative loss rates markedly. Even if singles had ended up in the 90s with twice the loss rate (say 4 to 2 per 100,000 FH), you would not lose markedly more aircraft over the life of the fleet.

As the General pointed out, the lower lifetime cost of the single-engine fighter can more than offset its higher lifetime loss rate. There are, however, three counterarguments. Firstly, many nations buy fighters in small numbers and use them for long periods, two decades or more. The lower loss rate of the twin will better sustain fleet size, whereas the single could decline into ineffectiveness. Readers may remember the period in the mid-90s when the USAF lost five F-16s in quick succession owing to engine failure. The failure, resulting from a manufacturing defect, was not in itself catastrophic and a twin could have got home on its remaining engine. Although the USAF could absorb such losses, most nations could not.

The twin-engined option, being a larger aircraft, will have more potential for upgrade of new weapons and systems. Thirdly, when second-hand aircraft are procured, the extra purchase cost of the twin-engined fleet versus the single option is unlikely to be a showstopper, and the higher lifetime cost may be acceptable given the preceding two arguments. Incidentally, the General’s second experience of engine loss involved a contained failure of a turbine blade in an F-15. He shut down that engine and recovered on the remaining unit. Had that happened in an F-16 the aircraft would almost certainly have been lost. Coincidentally, at the time of writing, the Taiwan Air Force had just grounded its F-16A/B fleet for the second time within a few months. An F-16 was lost in August with an apparent engine problem; this followed three other engine-related accidents since March 98. Issues with the P&W F100 turbofan previously caused the grounding of the US and Israeli Air Force F-16 fleets.

Sometimes, we use two engines because we have no choice. Airframes are designed around engines, but aircraft start as a collection of performance requirements. The speed, range and so forth that the customer wants are distilled into a number of engine parameters with thrust remaining a priority for fighters. If there is an engine that meets those targets in a solo installation then, on cost grounds, it will probably win. If not, then the huge cost of engine development will likely be prohibitive and will rule out the single option. A twin-engine selection could well be the only choice. The F-22 has two 35,000 lb (wet thrust) P&W F119 engines. There is no 70,000 lb class alternative in the military engine class. Both the Lockheed and Boeing JSF contenders use a single engine – a derivative of the F119 is sufficiently powerful and is the obvious choice for these projects where low cost is a crucial design goal.

Similarly, the Saab Gripen needs 12,250 lb dry and 18,100 lb wet thrust to achieve its performance requirement; a single RM12 (F404 –GE-400) makes sense. Puzzlingly, the AIDC A-1 Ching-Kuo uses two TFE1042-70 turbofans to provide similar thrust and roughly equal performance to the Gripen. Perhaps the specification emphasises survivability (or there is some export limitation).

There is a strong argument that air forces should choose a high-low mix of aircraft. The more capable fighters are costly and can only be procured in small numbers, whereas the cheaper aircraft will lack certain capabilities. Buying some of each should provide sufficient force size and capability to produce a truly effective fleet. If both types use the same engine, then large savings in maintenance, training, facilities and spares will accrue. Generally, the high-end fighter will be larger than its low-end partner. If both use a single engine then, to achieve reasonable performance, those engines must be of different types, and the duplication of support effort will be expensive. The best example of the common engine, high-low mix is the F-15 and F-16, both of which use the P&W F100. The later F-22 and JSF do not share a common engine, the Pratt & Whitney F135 of the F-35 being a distinct development from the F119 it is based on.

Saab’s Gripen E-series has adopted the F414-GE-39E turbofan, suggesting a good high-low mix, partnering it with the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet. The Russian MoD would ideally would like a future force of Su-57Ms twins and single-engined Su-75s both powered by the AL-51F-1. Interestingly, the Azerbaijani Air Forces will be operating the twin MiG-29 and the single JF-17 (with similar closely related engines) at least for a while simultaneously. The JF-17C Block 3 will be fitted with more capable equipment, giving the unusual situation of the high-low and low-medium mix.

An extension of this idea of community may be that a next-generation European ‘Loyal Wingman ‘-like the project would benefit from engine commonality with either Typhoon, Rafale or Gripen E, or perhaps more expensively, engine commonality with the next generation. Fitting a larger UCAV with an existing generation engine (such as the EJ200) may be a good move, as well as insurance against a cancelled ‘high’.

Paul Stoddart served as an engineer officer in the Royal Air Force for eight years. He now works for the Defence Evaluation & Research Agency (DERA). This article is his personal view on the subject and does not necessarily reflect RAF, Ministry of Defence or DERA policy.

NOTE: *The original article has been updated to reflect its date of 1998. I just found it sitting in the WordPress drafts folder many years after Paul sent it to me.