My sister sent me a link to a BBC News article about a new exhibition at Britain’s National Archives called “Great Escapes: Remarkable Second World War Captives” (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/great-escapes/). The exhibition is the culmination of an effort started in 2014 to catalogue and publish POW record cards which the Ministry of Defence had transferred to the National Archives. The exhibition website says the exhibition will attempt to explore “the human spirit in times of captivity.”

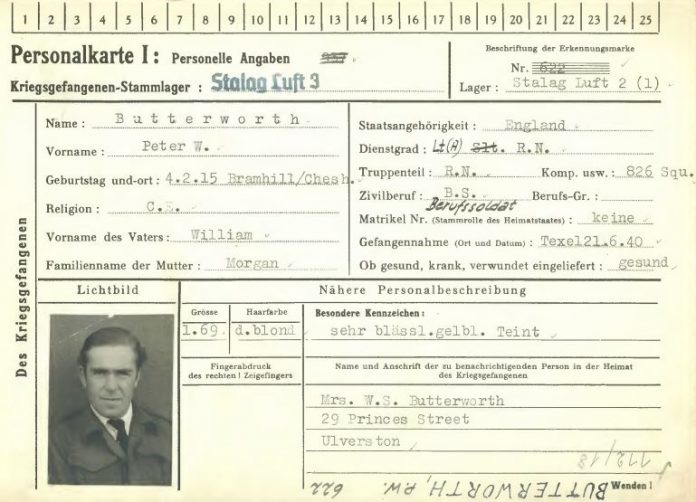

WO 416/53/114: Prisoner of War card for Peter Butterworth. It is worth noting that the Luftwaffe referred to the camp at Sagan as Stalag Luft 3 with an Arabic numeral. So did Paul Brickhill, author of The Great Escape who was imprisoned there. However, several classically-trained British Officers used the Roman form, and later an unknown English editor changed Brickhill’s text similarly, so Stalag Luft III it became, and thus it has remained in the collective consciousness. Public Domain via National Archives https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/opening-prisoner-war-collection/

Peter Butterworth

One particular record card seemed to attract the attention of the British news media. This card was Peter Butterworth’s. An RAF prisoner named Talbot Rothwell and Butterworth were instrumental in setting up the camp theatre at Stalag Luft III, and post-war their careers came together in a very British form of entertainment, the “Carry On” line of comedy films which Rothwell scripted between 1963 and 1974, and in which Butterworth played.

It’s interesting enough to see how a number of future entertainers first trod the boards courtesy of the Luftwaffe, but looking at these individual stories I discovered a little-known corner of British air operations in 1940 – the role played by the Fleet Air Arm covering the last phases of Operation Dynamo – the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from Dunkirk.

Butterworth’s POW registration card shows that he was a Lieutenant (A) RN in the Fleet Air Arm, flying with 826 Squadron, and was captured at Texel, northern Holland in June 1940. Looking up 826 Squadron in Wikipedia, I was a little surprised to learn they were equipped with the Fairey Albacore.

Fairey Albacore. The Albacore was intended to be a replacement for the venerable Fairey Swordfish, however both served together until replaced by monoplanes like the Fairey Barracuda and Grumman Avenger. Ironically the Albacore was withdrawn from first-line use before the Swordfish. Image from Aircraft of the Fighting Powers Vol I. Leicester, Harborough Publishing Co, 1940 (Public Domain)

826 Squadron was formed at RNAS Ford in March 1940, equipped with the new Albacore. Following training 826 was placed under the operational control of RAF Coastal Command to try and stem the tide of the Blitzkrieg. Flying from RAF Bircham Newton in Norfolk, the squadron’s first operations (and the first operational use of Albacores) were a series of daylight bombing raids on 31 May 1940 against road and rail communications at Westende and later against a road junction at Nieuwpoort, Belgium accompanied by Skuas of 801 Squadron.

On June 21st 1940, Butterworth’s Albacore, L7089 “4-R” was attacking coastal targets in northern Holland when it was shot down by Bf 109s. One of the three crew died of wounds sustained in the attack but Butterworth and his gunner survived. Butterworth was taken to Dulag Luft (Durchgangslager der Luftwaffe – the transit and clearing camp for British aircrew) at Oberursel near Frankfurt.

At Dulag Luft, Butterworth was appointed to the camp’s “permanent” staff by Wing Commander Harry “Wings” Day (Senior British Officer) where he joined a group of future “hard core” escapers such as Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, Lt. Commander John Casson, and Lt. Commander “Jimmy” Buckley. Buckley and Casson were FAA pilots shot down in May and June 1940 over Calais and Norway respectively.

Naval Aviators at Dulag Luft, Peter Butterworth is second from right. Also shown are John Casson and Peter Fanshawe whose 803 Squadron Skua was shot down over Norway on 13 June 1940 while attacking the German Battleship Scharnhorst. Both Casson and Fanshawe were central to the Great Escape from Sagan. (Public Domain, from the blog “The Magician of Stalag Luft III”)

I think there can be little doubt that Butterworth was an active member of the escape organization and was probably introduced to the art of coded communications with MI9, whose task was to assist allied airmen escape or avoid capture. Allied airmen passing through Dulag Luft were sometimes resentful of what they perceived to be of the “easy” life led by the British staff members. They were unaware that the staff had escape plans of their own. In June 1941 around 20 prisoners including Day, Buckley and Butterworth escaped through a tunnel, their third. All were recaptured and sent to Stalag Luft I in Barth where they were met with a cool reception until the reason for their arrival became known. As Barth became increasingly overcrowded a number of prisoners including the Dulag Luft cadre were transferred to a newly built camp, Stalag Luft III in Sagan, present day Poland.

Talbot Rothwell

On 14th June 1940, exactly a week before Petter Butterworth was shot down, Pilot Officer Talbot “Tolly” Rothwell took off from RAF Leuchars in Lockheed Hudson N7359 “QX-Q” of 224 Squadron, RAF Coastal Command. Rothwell was briefed to undertake a reconnaissance mission to Norway. He was destined not to return for a few years.

Lockheed Hudson Mark I T9277 of 224 Squadron based at Leuchars. Like Talbot Rothwell’s Hudson, T9277 went missing while on a patrol off Norway on 9 December 1940. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

N7359 was shot down by Anti-Aircraft fire over Stavanger. Rothwell and his co-pilot survived, but the other two crew members were never found. They are listed on the Runymede memorial for missing aircrews with no known grave.

Rothwell’s path to Stalag Luft III is not documented but he undoubtedly would have passed through Dulag Luft and was probably sent to another POW camp before being transferred to Sagan when it opened in 1942.

Once they met and teamed up at Stalag Luft III, Butterworth and Rothwell were instrumental in establishing the camp theatre. In a very British arrangement, the two were apparently told to give their word that they wouldn’t try to escape. A website about Rothwell claims that prisoners would not use the construction equipment and materials for the theatre for escape purposes. Undoubtedly the theatre project would have been scrutinized by the Germans but the arrangement does seem so very gentlemanly.

An incredible picture of the theatre at Sagan during its construction. Clearly visible are the Red Cross markings on the seats, which were made from the packing cases for Red Cross ration parcels. Peter Butterworth is standing at the very back of the group. (National Archives, Public Domain)

Stalag Luft III’s Senior British Office, Group Captain Herbert Massey, permitted sand from the tunnels to be stored under the tiered seating of the theatre after consultation with other senior officers in the camp. Butterworth and Rothwell were encouraged to make a lot of noise in rehearsals to cover the noise made by other prisoners involved in escapes.

After the war Talbot Rothwell returned to England and wrote radio scripts for The Crazy Gang, Arthur Askey, Ted Ray and Terry-Thomas. He wrote scripts for the British Children’s TV show Mr. Pastry and adapted George Simenon’s Maigret novels for television. By coincidence (or was it?) Maigret was played by fellow prisoner and performer Rupert Davies

Rupert Davies

Sub Lt. Rupert Davies was yet another FAA aviator shot down in the early stages of the Second World War while trying to foil Operation Sea Lion. Davies was a member of 812 Squadron embarked on HMS Glorious on patrol in the Indian Ocean. Glorious was recalled in April 1940 to support operations in Norway while 812 Squadron was disembarked and like many other FAA torpedo/bomber squadrons, placed under the command of RAF Coastal Command. Davies and his pilot Lt. (A) Nathanial Hearle were conducting a mine-laying operation (I assume at night) off the North coast of Holland in Swordfish L2819 when something clearly went wrong. On August 22 1940, a German coastal artillery unit discovered the two men floating in a dinghy off the Dutch coast, and during interrogation they admitted they were forced to ditch due to to bad weather.

Loading a mine on a Swordfish before a night operation. The long torpedo-shaped mine may come as a surprise for anyone who thinks of sea mines as those big round spheres with a lot of protruding knobs. (Public Domain via Australian War memorial)

I was curious as to why Davies and Hearle’s Swordfish had a crew of only two when it was normal for similar FAA aircraft to have crew of three. A contemporary article from the Sunday Express quoted in a Dutch website clarified the matter in no uncertain terms:

“Where the navigator ought to sit was an enormous petrol tank which stuck up between the pilot and the aft cockpit. The [observer] had to sit with his legs underneath a mass of petrol ready to drown him in flames if an incendiary bullet caught it. Now figure to yourself that sort of courage.

Carrying a mine which would leave nothing to pick up if it exploded and carrying a truck load of fuel to give it the thousand mile range, its speed such that the worst anti aircraft gunner or searchlight operator could hardly miss it. Its only protection against fighters the fact that it was too slow for them to stay with it and shoot at it.

They were the bravest men I have met. I have known a good many VCs and plenty of DSOs. None of these FAA lads had any decorations then. I hope they have got them since. Nobody admires our bomber crews, coastal reconnaissance people, and our fighter pilots more than I do. But those couples in the Swordfish deserve to be recorded in history for they made so much history themselves”

A Prisoner’s Journey. Screenshot of part of the MI9 debriefing for Rupert Davies’ pilot, Lt Nathaniel Hearle, showing the various camps in which he was imprisoned during his time as a POW (Public Domain via https://sites.google.com/site/wo2vpr1/home/1940-08-22-swordfish-i)

According to various websites Rupert Davies participated in at least three escape attempts during his POW career. A 2016 article in the Daily Mirror relates that while at Oflag IXA at Spangenberg Castle in 1941, he was bricked up in a window alcove for 21 days and then abseiled 100ft down the outside of the tower with a home-made rope. Nathaniel Hearle was involved in at least two tunnels at Sagan according to his debriefing with MI9 when he was liberated.

Rupert Davies – on the far right of the picture, on stage at the Stalag Luft III theatre in September 1942. Public Domain via Daily Mirror article March 2016

Rupert Davies trod the boards in the Sagan theatre and so did his plot, Nathaniel Hearle. A letter from Hearle dated August 1943 said: “The theatre will probably be finished next month. We have just started practicing Macbeth. I am taking the small part of one of the Sergeants in the 1st Act, one of the murderers.”

Following liberation, Davies had no desire to return to the Navy and took up an acting career, while Hearle returned to the Fleet Air Arm. Hearle returned to 812 Squadron as its Senior Pilot, flying the Fairey Firefly. While the Squadron was embarked on HMS Theseus on a tour of the Far East in 1947, he was killed in a flying accident over Melbourne, Australia.

Cy Grant

Cyril Ewart Lionel (Cy) Grant was born in British Guiana (later Guyana) and was one of only about 70 West Indian officers (and 400 aircrew in total) serving in the RAF following its decision to drop its color bar. Grant was the navigator in Lancaster I W4827 “PM-W” of 103 Squadron on his third operation. W4827 was on its return leg to RAF Elsham Wolds from a raid on Gelsenkirchen on June 25/26 1943, when it was shot down over Holland and crashed. Subsequent research has shown that W4827 had fallen victim to a Bf 110G of 10/NJG1 flown by Oberfeldwebel Karl Heinz Scherfling (KIA July 1944, 33 Victories), one of the Luftwaffe’s night-fighter “Experten.” Grant’s Lancaster was his third kill that night.

103 Squadron Lancaster III ED646 “PM-V” at Elsham Wolds, Lincolnshire in early March 1943. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205218709

Cy Grant describes his wartime captivity in his book A Member of the RAF of Indeterminate Race (Woodfield Publishing, 2006). A photograph of Grant with this caption appeared in the Nazi Party’s newspaper Völkischer Beobachter. I have to confess I haven’t read the book, but I plan to change that situation very shortly.

The start of Grant’s musical education at Stalag Luft III is described in a posthumously-published book by fellow prisoner Vern White of 427 “Lion” Squadron RCAF.

“Cy Grant is worthy of special mention. He was the tall, handsome RAF navigator from British Guyana who looked like Harry Belafonte. Cy was a versatile guy in sports and music. He was best known in camp for his renditions of West Indian songs and Broadway hit tunes with guitar accompaniment (his own). It started this way. Cy got his hands on a guitar from the collection of musical instruments on hand and would practice at the end of our hut. He was strumming away one day in front of an open window when an American Kriegie came by. He could tell that Cy was very much in the learning stage and asked if he would like some help. The American explained that he had played guitar in a famous dance band before joining up. Cy noticed that the Americans hands were heavily bandaged and learned that it was a result of severe burns when their B-17 caught fire after being attacked. His hands were so badly injured that it was doubtful that he would ever play guitar again. This condition did not prevent him from being an excellent tutor and Cy proved to be a natural.”

https://www.427squadron.com/book_file/white/four_years_stalag.html

Entertainment was not Grant’s first choice of postwar career. He was aspiring lawyer who completed his legal training but turned to acting and entertainment following his experience of racism in the British legal profession. In the 1950s, he became the first black personality to be featured regularly on British television. His musical contributions to the BBC current affairs show Tonight were one of the few ways that a current affairs show could comment on news events of the day. His personal website celebrates his life and activity until his death in 2010.

Donald Pleasence

Can I find a wartime image of Donald Pleasence? You have gathered from this 1973 portrait that I can’t. There are a couple of unsubstantiated images, but I can’t verify them. I’m not even going to try to include an image from The Great Escape, Image by Allen Warren CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

It is very difficult to think about Stalag Luft III without thinking of the 1963 Movie “The Great Escape” and the shy Photographic Interpreter turned forger Flight Lieutenant Colin Blythe played by Donald Pleasence. (Author’s note it has taken me well over 50 years to get his name right, it is Pleasence not Pleasance). It may not be so well known that Donald Pleasence was himself an RAF POW in the Second World War.

Flying Officer Pleasence was the Wireless Operator aboard Lancaster III NE112 “AS-M” of 166 Squadron flying from Kirmington on August 31 1944 when it was shot down attacking the V-2 depot at Agenville, France. Sources indicate Pleasence had flown “nearly” sixty operations before being taken prisoner. Obviously, he was quite a way through his second tour at the time. Perhaps another reader may be able to set the record straight! Pleasence ended up at Stalag Luft I in Barth. He seemingly started becoming active in theatrical productions there, and postwar was very much an actor in demand.

Postscripts

There are one or two humorous postscripts to these stories:

Peter Butterworth exercised in Stalag Luft III using a very famous wooden vaulting-horse while three of the other prisoners dug a tunnel starting from the wooden horse’s location. When a movie version of Eric Williams’ story The Wooden Horse went into production Butterworth apparently auditioned for a part, but was rejected because he didn’t look “heroic or athletic enough” according to casting.

Donald Pleasence offered technical advice to John Sturges, the director of The Great Escape and was told to keep his opinions to himself. Another cast member pointed out that Pleasence was a genuine RAF POW, and indeed the only member of the cast with that distinction.

Talbot Rothwell wrote a screenplay for a “Carry On” film in 1973 that was never made. It was called – you guessed it – Carry On Escaping, and was to be a send-up of the 1950s and 60s escape movies complete with the bawdy humour and double-entendres so familiar to the genre. The screenplay still exists can be found in the book The Complete A-Z of Everything Carry On. Some information can be found on the TV Tropes website

Great Escapes: Remarkable Second World War Captives runs from Friday 2 February 2024 to 21 July 2024 at the National Archives and is free.